Vermont. February 01, 2010.

Fly casting from a canoe in the middle of a small pond at the tippity-top of the headwaters of the Connecticut River is usually an all quiet experience. The loud splash caused me to turn just in time to see the osprey struggling up out of the water. I thought at first it had made a mistaken pass at a fish and splashed down instead of plucking the fish out of the water and flying off. It was unsuccessful in capturing a fish.

The bird circled up into the air maybe 30 feet above the water and began to fly loosely in a circle. It had my attention, and soon it made an instant, wings-folded, headlong dive for the water. But instead of expanding its wings and grasping acrobatically with its talons for the fish it went head first into the water, again with a loud splash.

Ignorant of the osprey fishing technique at the time, my thoughts were that this particular bird had a problem and it must have given itself a throbbing headache from smacking into the water head first at full speed diving for its fish. Part of the problem for the osprey was it was a cloudy windy day, and as any fisher, human or animal knows, you see into the water more clearly on bright days from a height above water when the surface of the water is calm. It still had not hooked its fish.

It flew up to a branch hanging over the pond and sat majestically watching the pond like a hawk. Actually the osprey (Pandion haliaetus), meaning sea hawk in Greek, is not in the hawk family but its own family. The bird is still known as the fish hawk and is unusual in that it is a single species that occurs nearly worldwide and is found on all continents except Antarctica.

Fortunately, the osprey is superbly designed to capture fish since fish comprise more than 95 percent of its diet. Their feet have reversible outer toes and small hard needle-sharp spicules on the underside of the toes, closable nostrils to keep out water during dives, and backwards-facing scales on the talons which act as barbs to help hold its catch. The outer toes allow the osprey to align a captured wiggling fish with the line of flight of the bird. The spicules and scales help the bird to hold on to its slippery prey.

As to the head-first splash, as the only raptor that plunges into the water, osprey dive with their feet on each side of their head allowing them to keep the fish in sight all during the dive with the feet cutting through the inelastic water surface avoiding the headache.

It is thought that ospreys mate for life. The situation seems to be, though, that they are loyal to their nesting site and usually return each year to the same nest. If one of the pair does not return, another mate is quickly found. Female ospreys usually winter farther south than do their male counterparts, and individuals of both sexes display strong fidelity to wintering areas.

Most Connecticut River osprey winter in South America, although some only migrate as far as the Florida Keys. Those birds going further will go from the tip of the Keys, over to Cuba and then on to Hispaniola. Some stop there and winter in the Caribbean islands, but the majority make the trip across the Caribbean Sea to Venezuela. Males and females take separate routes on their migration. The young do not follow their parents but travel on pure instinct when they head south.

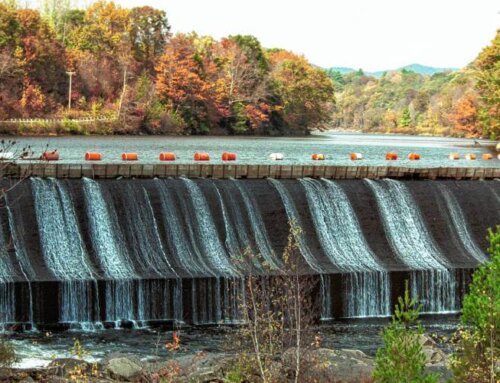

The mouth of the Connecticut River contains the highest concentration of breeding ospreys along the southern New England coast. In the early 1940s there were approximately 200 nesting pairs of ospreys at the mouth of the Connecticut River. Populations steadily declined to only a few pairs by early 1960s due to DDT exposure. The latest figures available show there are 43 active nesting pairs in the lower river in 2001, just over 20 percent of the 1930-1940 population, a shadow of their former abundance.

The osprey population in the upper Connecticut River watershed is also in the early stages of recovery. Only the northern reaches of the watershed in Vermont and New Hampshire have active nesting sites. Vermont and New Hampshire field studies show no active nesting attempts documented in the southern two thirds of the upper Connecticut River watershed.

The use of DDT has been outlawed in America so most of us think that that threat to ospreys is long gone. Unfortunately, because ospreys are long-distance migrants they are exposed to DDT in prey species during migration and in the wintering areas. One threat closer to home to their full recovery is consuming lead sinkers along with their fish, subjecting them to lead poisoning. Continued use of lead fishing tackle (in violation of the law in both Vermont and New Hampshire) could threaten the recovery of our ospreys so “get the lead out!”

Back on the pond, the third try was the charm. The osprey fell out of the tree as though shot, diving straight into the pond head first and on reappearing had a fish tenuously gripped between two talons. It quickly put the fish in both feet, oriented it straight ahead, and despite the wiggling of the fish, the bird held on and flew off. I on the other hand did not land a fish that day.

David Deen is River Steward for the Connecticut River Watershed Council. CRC has been an articulate voice for the Connecticut River for more than half a century.