The Long Island Sound River Restoration Network (RRN), a network of Connecticut and New York-based organizations including Connecticut River Conservancy dedicated to the restoration and health of the region’s rivers, has released their Dam Removal Report. The report summarizes the benefits of removing dams to restore free-flowing rivers in the Long Island Sound watershed and showcases a dam removal site that has rebounded with native flora and fauna.

There are around 5,000 dams in Connecticut, equating to nearly one dam per square mile. In the New York portion of the Sound’s watershed, there are nearly 200 dams. Dams were once built to divert or hold water for hydroelectric facilities, recreational use, navigation, water supply, and mechanical power purposes. While dams once held a purpose, most have become inactive and now act only as barriers to the natural function and flow of rivers.

“The reasons we remove dams are not always clear to the general public,” says Laura Wildman, vice president of ecological restoration at Save the Sound, a member of the RRN. “Dam impacts often go unnoticed because many are beneath the water’s surface. This report answers the question, ‘why should we remove dams that no longer serve their intended purpose?’”

Dams pose several threats to our ecosystems, including interference with the migration of fish species that need to travel between saltwater and freshwater to reproduce. Many of these fish are keystone species, essential in the food chain. Their undisturbed passage through our waterways contributes to the overall health of our rivers, estuaries, and oceans.

Along with ecosystem interruption, dams pose a threat to nearby communities. Dam failure can lead to infrastructure flooding and the release of polluted sediment. With storms increasing in severity and many aging dams left unmaintained, the risk of dam failure is greater than ever.

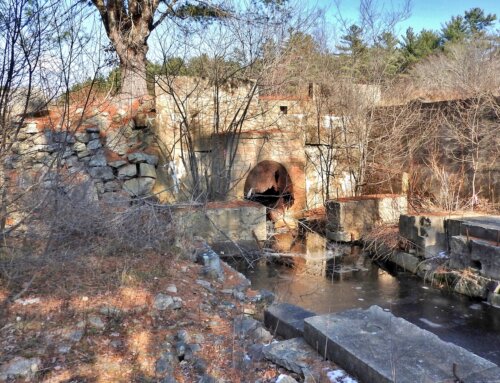

The RRN’s Dam Removal Report explores the importance of free-flowing rivers and what happens once a dam has been removed. A case study is provided, using a past dam removal project on the West River in New Haven, Connecticut to illustrate how free-flowing rivers can decrease flooding, provide fish passage, and improve water quality.

Pond Lily Dam was located on a highly developed portion of the West River. Removing the dam reconnected 2.6 river miles, reduced flood risk, and restored habitat. Post removal monitoring showed that 76 acres of habitat were restored, and 60 times more alewife—a critical species of migratory fish that requires access to riverine habitat to reproduce—were present in annual fish runs five years post removal. Native wetland plants rebounded in the dam’s former pond impoundment, which contributed to increased biodiversity and resiliency.

The Long Island Sound River Restoration Network is a group of nonprofits working together to accelerate the pace and scale of stream barrier removal (in addition to dam removal, this includes replacement of undersized or misaligned culverts). Members include American Rivers, Connecticut River Conservancy, the Farmington River Watershed Association, the Housatonic Valley Association, The Nature Conservancy, Save the Sound, Seatuck Environmental Association, and Trout Unlimited. By collectively developing projects, sharing resources, communicating benefits of restored river systems, and coordinating with regulators and funders, the RRN is building regional capacity, resources, and support for dam removal.

“It is exciting to have a collaborative report that all River Restoration Partners can share,” says Emily Hadzopulos of The Nature Conservancy. “The dam removal report provides an engaging and succinct overview on why free-flowing rivers are important to Long Island Sound and how we can achieve free-flowing rivers through projects like dam removal.”

Read and download a copy of the report from Save the Sound’s website.

The Dam Removal Report was funded by the Long Island Stewardship Collaborative Fund at the Long Island Community Foundation.