Written by Kate Buckman, Connecticut River Conservancy River Steward in New Hampshire

Floodplains are for the birds!

And for improving water quality, mitigating flood waters, and providing needed organic material among other things… But, today we’re talking about birds. Big birds. Birds with striking hairdos. Birds that are quite social despite their appearance of RBF (resting bird face). You may have been tipped off by the lead photo… we’re talking about Bald Eagles!

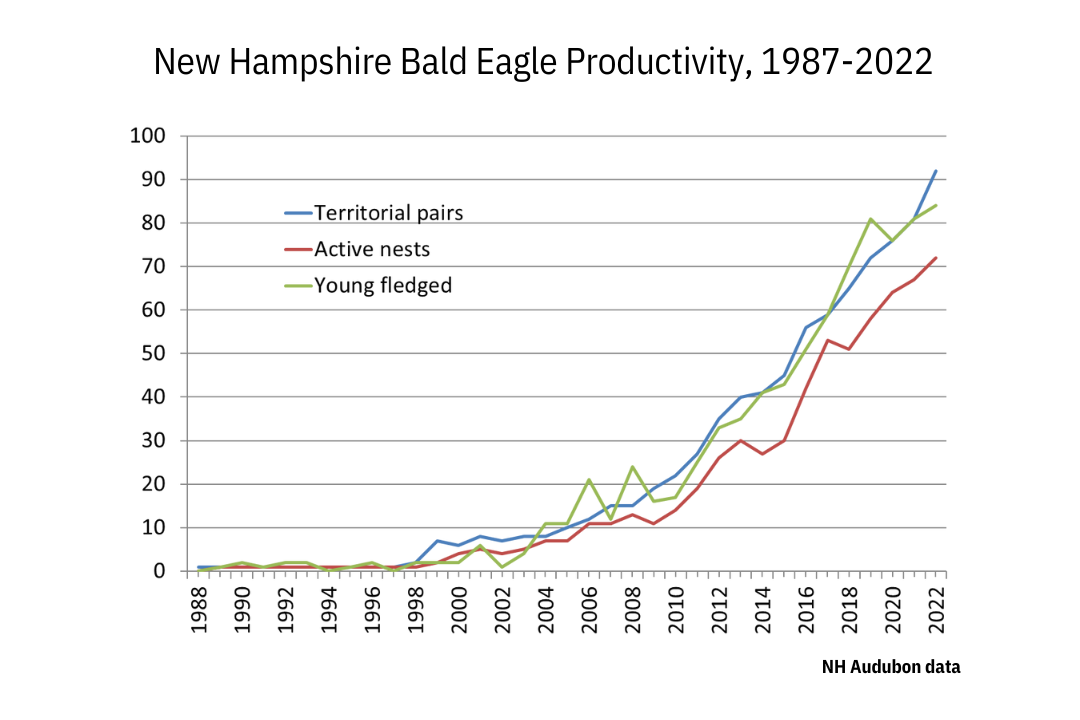

Bald Eagles (Haliaeetus leucocephalus) have made a dramatic recovery in New England since they gained federal protection in the 1970’s and were reintroduced in western Massachusetts in the early 1980’s. The first nesting pair reappeared in New Hampshire less than a decade later. Within my lifetime we have gone from zero nesting Bald Eagles in New Hampshire to over 90 breeding territories across the whole state in 2022 (see the graph below).

On the mainstem Connecticut River, including both the New Hampshire and Vermont sides, approximately 32 nests currently stretch from the headwaters on the Canadian border all the way to Hinsdale and the Massachusetts line. That’s a remarkable wildlife restoration success story!

I knew about the positive impact banning DDT had on Bald Eagles, but I was curious what else had helped contribute to the population increase. To find out more about Bald Eagles in general, I contacted Chris Martin, a conservation biologist at NH Audubon, who has spent the past 30+ years monitoring Bald Eagle populations for NH Fish and Game and VT Fish and Wildlife with the help of many community volunteers. Together, they have amassed a large amount of information and photos (like the one above by volunteer Chris Roberts) regarding the productivity, nest locations, and population numbers of Bald Eagles in NH and overlooking the river in VT.

Bald Eagles need access to water. They are generalists in terms of diet, eating anything they can get their talons on from roadkill carrion to other birds. But, they really love fish. They build their nests on the banks and in the floodplains of rivers or the periphery of lakes and ponds. These locations provide access to fish and a good perch to observe their surroundings.

In NH, these nests are found almost exclusively in large white pines or cottonwood trees. These trees are branchy and able to support the nest, which can reach 8 feet across and 5-6 feet deep. There is often a secondary alternate nest tree nearby in case of a catastrophe occurring to the primary nest. The nests are used repeatedly, though not always by the same eagles. Chris knows of one nest in Plainfield that has been used continuously since 2000.

The eagle pair will spend the fall and winter adding sticks and branches to their chosen nest, repairing damage that occurred over the summer getting it ready for the next season’s chicks. Breeding season begins in February with courtship, mating, and often egg laying occurring by the end of the month. Eggs hatch about five weeks after they are laid and for the next twelve weeks after that the parents are busy feeding and caring for their young. During this time, the eagles will only add material like grass or hay to the nest to keep the chicks warm and dry and the nest can often visibly deteriorate from lack of stick maintenance. After fledging in the late summer, the young Bald Eagles are still dependent on their parents for a few more weeks before heading out on their own.

Caption for above: Chris Martin releasing a juvenile Bald Eagle. Photo credit David Lane: Union Leader. Caption for header image: Bald Eagles nesting pair observed in Bellows Falls VT. Photo credit Chris Roberts.

While the young will travel far and wide in search of their new home, adult Bald Eagles stick around all year in their chosen community. They are fairly social with other eagles, and don’t have as large a territory as I would have expected. They are defensive of their nests when chicks are there and maintain a territory within about half a mile of the nest but are not particularly aggressive about it and will happily nest within sight of multiple other eagle pairs. The Bald Eagle population in NH has doubled about every six years since they were reestablished (see the graph above), and during that time the CT river eagles just filled in blank spaces on the map, basically halving the distance between eagle nests every time a new breeding territory was established around an available nest tree on the mainstem.

When I asked Chris what his favorite thing about Bald Eagles is, he laughed a bit (I’m probably not the first person to ask), then indicated that one of the things he appreciates about them is their resourcefulness. They have the ability to learn about their environment and live long enough to really take advantage of and utilize that knowledge. He compared the eagles to our neighbors and noted that just like we do in our own neighborhoods, Bald Eagles learn where to go and where not to, the good shortcuts, and the best spots to eat. It seems to me that this resourcefulness and adaptability has likely been one key to their successful repopulation in NH and New England in general.

The Connecticut River valley with preserved and restored riparian buffers and forested floodplains provides needed nesting and wintering grounds near to water while open farmlands dotting the landscape also ensure space and additional food sources. The watershed provided what the Bald Eagles needed; Chris remarked that “we humans just needed to get out of their way.” A good reminder for all of us that advocacy and work to maintain and restore healthy water quality, ecological function, and access to river ecosystems improves everyone’s neighborhood, Bald Eagles and humans alike.

If you are interested in using your “eagle eyes” to help monitor Bald Eagle nesting pairs in NH, please contact Chris Martin at cmartin@nhaudubon.org. If you have any questions for me, you can reach me at kbuckman@ctriver.org, and if you are thinking to yourself “Kate, I was promised I could work with fish” Never fear! We are gearing up for our community science initiatives across all four states this coming spring. More information can be found here.