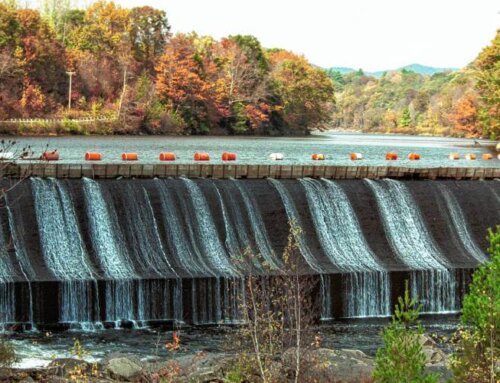

The owner of three dams in the upper valley is seeking Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) relicensing. For most, the relicensing of three hydroelectric dams is not exciting news but quite honestly this is a once in a lifetime opportunity to work for the Connecticut River. A little history might help in understanding why this is such a remarkable opportunity.

In January 1971, the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) became law. It initiated quite an important change in the hydropower licensing process. Pushed by the outcry of the Santa Barbara California oil spill and Rachael Carson’s “Silent Spring,” the US Congress passed NEPA. Along with other provisions, NEPA requires an Environmental Impact Statement whenever the federal government issues a license, spends money on a project, or takes an action on its own. NEPA requires FERC look at more than just the maximum amount of power produced at a generation facility. FERC now must look at a project’s environmental impact.

The process underway in the upper valley involves three dams, Wilder, Bellows Falls and Vernon. To complicate matters a bit more, there are also two additional hydro facilities although owned by a different company undergoing relicensing on the same exact schedule in MA but that is another story. The reality is there are five facilities undergoing FERC review at the same time that affect over 175 miles of river through their reservoirs alone. Flow manipulation at the Northfield affects the river for miles above and below the pump storage facility.

The last license issued to all of these facilities was 40 years ago, so they predate the full implementation of NEPA. When last licensed, these facilities did not need to meet the NEPA required balance between environmental impacts and power production. These applications for relicensing, if successful, will lock the power production and environmental impacts in place for the next 40 years. When you think about what happens to a river when there is a dam across it, 40 years is a long time and this effort to make dam operations better is a big deal with long lasting results.

The most straightforward way to insure the natural health of the river is to yank the dams out of the river and be done with it. That option has not been put forward by anyone and is not being talked about in the FERC process. These are important electric power and economic assets to our valley so the dams will stay. Yet our knowledge over the past 40 years about rivers and how to achieve healthy river conditions has grown exponentially. This new and more powerful understanding should apply to these facilities.

In order to think about what should change in the operations of the facilities you have to understand the condition of the river right now. Once you have a handle on that, you can begin to talk about how to improve things. Establishing current conditions will put a large flock of consultants to work on the river in 2014 and 2015. Guiding the consultants are study plans. These set out what is to be studied and how the consultants should conduct their fieldwork. The plans are developed by people with an interest in the facility operations like Connecticut River Watershed Council (CRC) and state and federal resource agencies, who met with FERC and the applicants for 18 months to discuss what the consultants should look at out there on the river.

So, the study plans are not invented out of whole cloth. They are the results of requests from groups like federal and state Fish and Wildlife agencies, water quality agencies, first Americans tribes, historic preservation interests, recreation groups, landowners and watershed organizations like CRC based on the owners’ preliminary application for relicensing. In the preliminary application, the owners present everything they could to FERC about each of the facilities. We reviewed the applications, thought about missing information necessary to make informed recommendations to FERC and then made our requests for study plans. Among the five facilities, there will be over 60 field studies conducted between now and December 2015, hence the flock of consultants.

Examples of the studies are evaluations of shoreland erosion, modifications of water temperature and dissolved oxygen, model of river flows, dewatered bypass reaches, fish assemblages, fish access to spawning areas, affects of flows on over all aquatic habitat assessment, up and downstream passage for fish including the American eel, and effects of the dams on known threatened and endangered species. The stakeholders using the field study reports will compare and contrast the report findings with the best science known about the issue and become the basis for potential changes in operations of the facilities.

Thanks to NEPA, changes necessary to make the river healthier are now part of the relicensing discussion. The license process offers a chance to talk through FERC with the project owners about potential mitigation of the facilities’ impacts on the river. This long and complex process stretches five and a half years from start to finish. Watch this space for updates on the latest developments as this process moves forward.

David Deen is River Steward for the Connecticut River Watershed Council. CRC has been a protector of the Connecticut River since 1952.