A recent study about “forever chemicals” in freshwater fish has made national headlines, reporting that eating just one freshwater fish a year is equal to a month of drinking water contaminated with chemicals linked to cancer and other adverse health effects. The study from Environmental Working Group showed that locally caught freshwater fish across the United States are likely a significant source of exposure to PFAS and other perfluorinated compounds to people who consume them. Given our strong connection with the Connecticut River and tributaries, we thought we’d take a closer look at the data along with other local research to see what conclusions we can draw from this about the waterways in New England.

For those who want the quick takeaway, our general assessment is that PFAS are an issue in the Connecticut River watershed just as they are across the country. States are working on monitoring and regulating PFAS and issuing consumption advisories (such as this factsheet and this advisory in NH) or monitoring plans when appropriate (such as this plan in VT). Consuming freshwater fish from local waters can be a source of PFAS exposure but it is just one among many ways we can and are exposed to PFAS every day.

What is PFAS?

PFAS is short for per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances and refers to a group of over 4000 human-made chemicals found in everyday household products such as nonstick pans, food packaging, waterproof jackets, and carpets, as well as personal care items such as shampoo and shaving cream, and even industrial materials such as aqueous film forming foam used to fight fires at military bases and commercial airports. One subclass of PFAS, perflourooctane sulfinates (PFOS), are often the focus of exposure due to their widespread use and persistence in the environment.

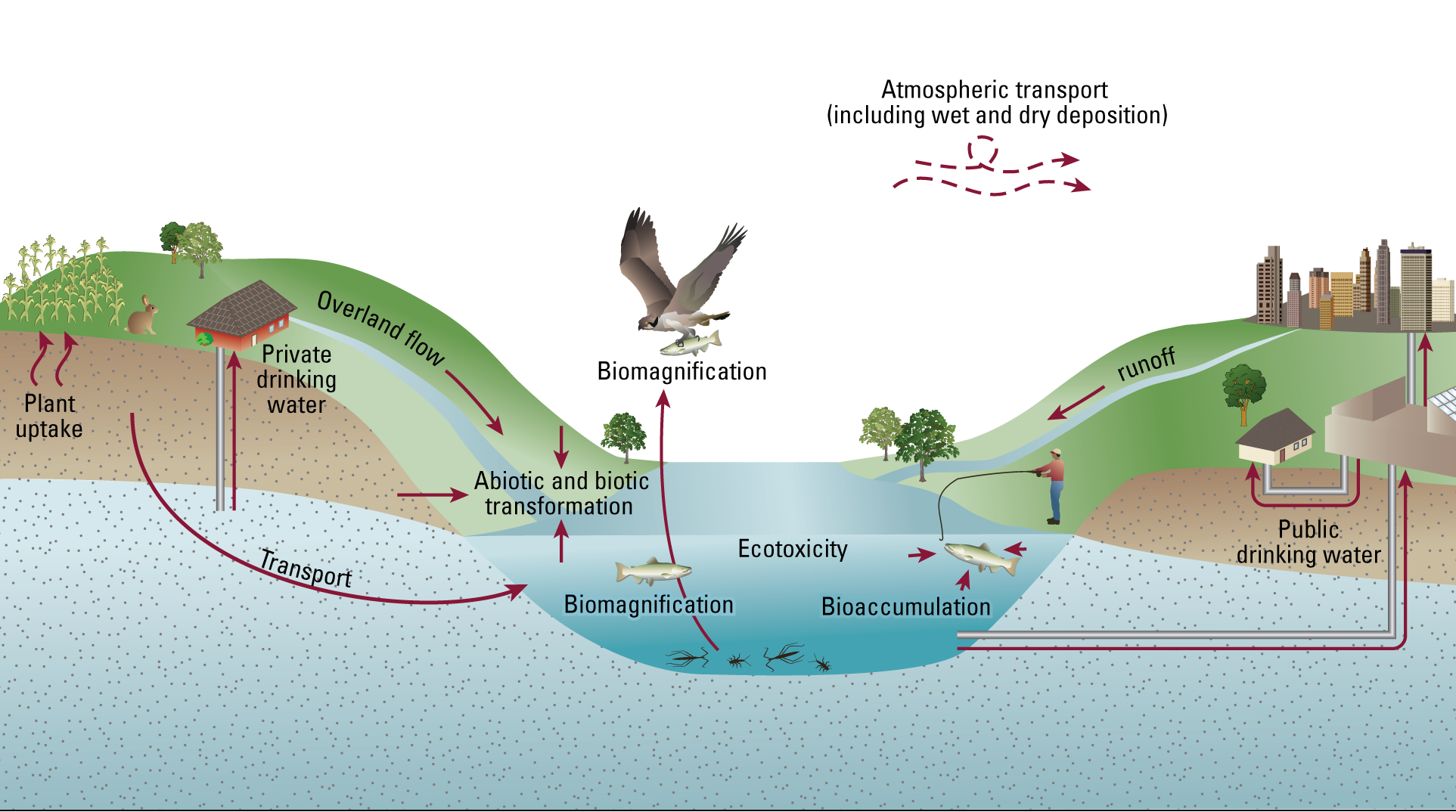

PFAS compounds are useful because they are designed to be resistant to breakdown and impart stain and water-resistant properties to products. Unfortunately, they continue to resist breakdown and become “forever chemicals,” persisting in the environment for decades. They can bioaccumulate (accumulate in tissues) and biomagnify (increase in concentration as you move up the food chain) in living organisms resulting in negative health effects, including cancer. For these reasons and more, they are a serious contaminant that is a global problem.

Per-and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances movement through the environment (source: USGS)

The New Study:

First, a summary of the key takeaways from the new Environmental Working Group study:

Researchers reviewed data from over 500 samples of fish fillets collected under various other studies in the US. Freshwater fish data came from two different US EPA monitoring initiatives analyzed in 2013-2015. One of these studies targeted fish from the Great Lakes region, which should be noted, is home to several industrial producers of PFAS; Great Lakes fish had a higher concentration of PFAS than more generally across the US. The study concluded that consuming freshwater fish caught in the US can significantly increase PFOS concentration in the human bloodstream, compared to exposure from drinking water alone. They point out that this is an environmental injustice that affects communities that depend on freshwater fishing for sustenance and for traditional cultural practices, which often includes poor, underserved, or BIPOC communities which may be subject to additional environmental health hazards as well.

One thing that is important to understand about PFAS both locally and nationally is that this is an emerging area of science. There is, unfortunately, a lot that scientists don’t fully know or understand yet about PFAS, how they move through the environment, and the full effects of chronic exposure on humans, wildlife, and the environment. Even analytical methods for accurately measuring the different PFAS compounds are still being developed and refined. If you are concerned about PFAS, it will be important to keep up as new science emerges and puts what is understood currently into context. For example, there are no federally agreed upon standards in the US for exposure to PFAS through water, eating, or household use yet. The research needed to set these standards is still being done. Individual states have enacted drinking water standards and have issued fish consumption advisories where they feel it is appropriate, but these will likely be adjusted as our knowledge regarding the environmental health effects of PFAS increases.

- Falls in the Connecticut River below Second Connecticut Lake, Pittsburg, NH. Photo by Al Braden.

- Westfield River at Chesterfield Gorge, MA. Photo by Diana Chaplin.

- Skyline and Connecticut River at Springfield, MA. Photo by Al Braden.

PFAS in the Connecticut River Watershed

While this research is helpful in looking at the issue on a national scale, let’s turn to other studies done closer to home. We reviewed the information available from our four watershed states (VT, NH, MA, and CT). Unfortunately, PFAS are found everywhere that scientists go looking for them – groundwater, surface water, fish, animals, humans, etc. Testing for PFAS is incredibly expensive and challenging.

Because PFAS are used in many household and laboratory products, extra care is needed to ensure there is no contamination during the sampling and analysis compared to other things that might be tested for. Even with these challenges, all four states have their own testing programs for water, fish, and more. Here’s a look at how each state is approaching PFAS in their surface waters:

- Vermont released a surface water monitoring report in 2021 and is expected to go through the rulemaking process to issue water quality standards in 2024.

- New Hampshire added PFAS monitoring to their surface water monitoring in 2017 and developed a plan to create water quality standards in 2019.

- Massachusetts funded a study along with the United States Geological Survey (USGS) which focused on known point sources in the eastern portion of the state but included some sites in the Connecticut River watershed.

- Connecticut is developing a mapping tool to identify potential PFAS sources and guide future monitoring efforts in the states’ waters.

What About PFAS in Fish?

There are varying levels of PFAS in local fish depending on their environmental exposure and location on the food chain. Fish in water bodies located near point sources of pollution will have higher tissue PFAS concentrations than those caught in water bodies that are subject to background contamination. Some states (like NH and CT) have analyzed fish tissues in areas of known increased environmental contamination and issued consumption advisories for specific rivers and lakes. Currently, there is a fish consumption advisory for fish caught in the Hockanum River, a tributary to the Connecticut River in Connecticut. There was previously a similar advisory on the Farmington River, another tributary in Connecticut, after an aqueous film firefighting foam spill in 2019; this advisory was lifted in 2020 after testing showed reduced PFAS concentrations in Farmington River fish. More advisories may be issued as states are able to include more water bodies in their testing programs.

The suggestions for avoiding excessive exposure to PFAS from fish that are caught from local rivers and lakes are similar to those for avoiding other environmental contaminants that biomagnify such as mercury:

Eat low on the food chain, vary fishing spots, and respect local fishing advisories.

Fish that live in waters that have lower levels of PFAS contamination will have lower PFAS concentrations in their tissues. Because PFAS are so pervasive, the only way to avoid exposure from consuming locally caught fish is to practice catch and release.

Smallmouth bass, a common fish in the Connecticut River.

That said, PFAS are everywhere in our current world and will continue to be. Every day products like food packaging and waterproof clothing that contain PFAS continue to be manufactured and used nearly ubiquitously throughout the world. The unfortunate and scary truth is that we are exposed to PFAS in many ways every day, not just by consuming freshwater fish. Exposure to PFAS will only truly be addressed by discontinuing use of PFAS compounds globally, however, PFAS that are already present in our environment will continue to persist.

Connecticut River PFAS Conclusion:

While it is concerning to see viral headlines about the levels of PFAS in our nation’s fish, it is a reminder that these forever chemicals are a clear and present health threat in our modern world. It is a complex issue with a lot of different moving parts. Officials in our watershed states and national agencies are working hard to assess the current levels of PFAS in our waters, soils, fish, and more to set rules and regulations that will help keep folks safer. Ultimately, this is the best thing we can do to address this national issue and stop PFAS from entering the environment in the first place.

What CRC is Doing to Clean Up Our Rivers

CRC is aware of and following research and data collection efforts regarding pollution and contaminants in our watershed, from e. coli to excess nutrients to chemicals like PFAS. We work with state and local governments, industries, and other non-profits to address issues as appropriate. For example, one of the roles of our River Stewards in each state is to comment on discharge permits through the National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES). Anyone discharging a potential pollutant into a body of water must go through the NPDES permitting process, including a comment period. These permits now include regulations for discharging PFAS along with the other pollutants that they regulate. Our River Stewards review these permit applications and submit comments to help ensure that our rivers are protected. We regularly share all CRC comments via our News Updates.

Because of the difficulty and expense required to sample and analyze for PFAS, it is unlikely that CRC will start its own PFAS monitoring program. We will, however, continue to watch and engage with the studies being done by state and federal agencies about PFAS in the Connecticut River watershed, advocate for meaningful policy change at every opportunity, and educate the public. Please reach out if you have additional questions and we can connect you with the appropriate agency official for your state if we cannot answer them.

_______________

Written by Ryan O’Donell, Monitoring Program Manager at Connecticut River Conservancy

Editorial support from Kate Buckman, River Steward in NH, and Diana Chaplin, Communications Director

Sign up for email updates to get stories like this in your inbox