Each week, Connecticut River Conservancy volunteers go out to their local tributary rivers in the Connecticut River Valley to monitor for river herring as the fish return to freshwater ecosystems to spawn. These dedicated volunteers provide CRC, the CT Department of Energy & Environmental Protection (DEEP), and other partners with valuable data to track where river herring are present and absent. DEEP monitors at several locations in the watershed, and this joint program helps to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the health of our river herring populations. Many thanks to our partners and volunteers who give this program life!

Fish Update from the waters

Written by Steve Gephard, former fisheries biologist with the CT Department of Energy and Environmental protection.

This spring has been abnormal, but we often wonder if there is really such a thing as normal anymore. Without the amount of snow we traditionally saw in the the 1970s and 1980s, normal has taken on a different meaning. The Connecticut River ‘normally’ averages 35,000 cubic feet per second (cfs) at this time of year; however, the river is currently at only 9,000 cfs. The low flow may increase the warming of the water and allow migrating fish, such as river herring and American shad, to get upstream more quickly and easily. Flow also helps draw fish into a river as an attractant. Fish like river herring and shad probably don’t have too much trouble finding the Connecticut River but with such low flows coming out of the tributaries, it could result in river herring ‘overshooting’ or missing their home tributary.

Typically, the alewife run extends from the first of April to the end of April while the blueback herring run typically began the first of May and extended well into June. But times have changed. This year, Alewives were in the river by mid-March and the bluebacks were all the way up the river to the lower Farmington River by April 10th. The American shad are also already being passed over the Holyoke Dam, indicating that species got a quick start as well. Climate change, low flows, or perhaps other factors could be the cause of this early migration.

The fisheries staff at the CT Department of Energy and Environmental Protection (DEEP) monitor the river herring runs using electronic counters and staff at fishways. So far this year, DEEP’s counts show that the alewife run has been very disappointing relative to other years. Only handfuls have been seen in the tributaries, and even the large runs along the Connecticut coast are low. Bride Brook often logs runs between 300,000 and 400,000, and so far, only 171,000 have returned; but there still is time. In 2020, the last week of April showed a big influx in herring, so we still could get another wave in the coming weeks. Increased flow and water temperature bring in fish, and we are forecasted to get quite a bit of rain between now and Sunday. Next week there will also be a big warm up, so these weather patterns may provide the alewives with one last push, while the bluebacks could really get cranking next week along with the shad.

Volunteers do a great job of keeping an eye on the tributaries where agency biologists cannot cover. Seeing no fish day after day can be discouraging, but zeroes are important data, too. As we try to figure out trends in the runs, knowing where river herring are and are not is important. Sometimes it may be more common to see alewives enter small streams at night whereas blueback herring can be seen in abundance at any time. Daytime observations often require polarized sunglasses to cut the glare. Nighttime observations require a strong flashlight—and keep it moving. The light will scare the fish so you want to scan the water and look for darting forms. Alewives most often enter streams that have ponds or still water upstream. They spawn in ponds so a stream that lacks a pond—like Roaring Brook of Connecticut—may not draw in many alewives whereas Stony Brook, with an upstream dam and pond (that the alewives can smell) may draw them up, as well the swampy nature of the lower Mattabesset River that also is good spawning habitat. Blueback herring, on the other hand, spawn in flowing water and might be seen in places like Roaring Brook or the Salmon River. This coming week, I would guess that practically any stream might have both species. New volunteers are unlikely to be able to distinguish between the two species so don’t worry about it. Make your observations of river herring, document the date, time, and conditions and let the biologists speculate on which species are there.

Happy Earth Day.

Steve Gephard

Volunteer River Herring Data from April 7th -18th

This marks the first week CRC volunteers went out to their monitoring sites to observe the presences or absence of river herring across nearly 20 different

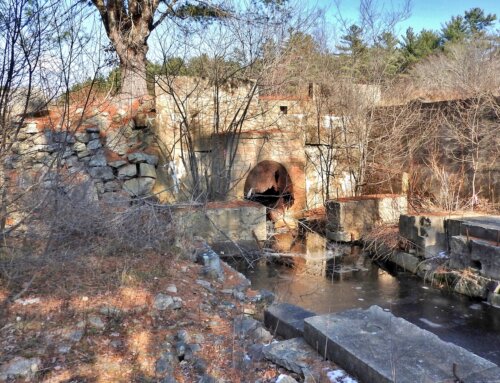

Photo Credit: L. Borla

locations. Altogether, these dedicated volunteers reported an impressive 71 data points! Though most volunteers didn’t see any river herring, many reported on the other wildlife seen at their sites and enjoyed spending a few minutes by their rivers, observing its flow. The link below displays a map of the 71 data points reported this week, showing where river herring were found and in what quantities (the darker, the higher the quantity of herring).

To see the full list of data reports, click the down arrow next to the pin icons and scroll down. You can also click on each pin to see more details and notes, if they were recorded.

Featured Site: Wethersfield Cove, Wethersfield CT

Wethersfield Cove is a beloved site along the Connecticut River, attracting anglers, boaters hikers and bikers, or simply bringing communities together at Cove Park. Of course, Wethersfield Cove as we know it today is much different than it looked even a few hundred years ago. Notably, a major flood in the late 1600s swept through what was once a bend in the river, taking several buildings with it and creating the present-day cove. This was the site of a bustling industry town and now serves as a recreational epicenter along the Connecticut River.

Bill and Paul, two river herring volunteers, have collectively been out to observe for river herring an impressive 14 times so far this season. Here is what they have to say about the cove and their monitoring expeditions:

Paul and his son observe Wethersfield Cove for river herring. Photo credit: Paul W.

“The work is optimistic by nature: ‘if you take the dam down, they will come.’ However, it remains to be seen if we are removing enough obsolete dams fast enough to reverse the wholesale decline in our fisheries. Fish ladders, while helpful in select cases, provide artificial constrictions in the migratory fish run. I was happy to take this opportunity to monitor the status of river herring migration and observe first-hand our progress in a way that does not rely on those constrictions. I’ve also been gradually exposing my two young sons to the great outdoors, participating in clean-ups, and now am happy that one will be accompanying me on these morning checks.” Cheers, Paul

“Volunteering as a community scientist in CRC’s river herring survey program is a great jumpstart to the CT River boating season for me. Getting out to Wethersfield Cove is enjoyable for me at all times of the year; but is a particular treat in the spring…doing so with a purpose. Walking the shores and encountering heron, cormorant, osprey and eagles returning to their summer stomping grounds is super encouraging and enjoyable to see. I’ve observed some disturbances of baitfish at the surface and seen a fish jump and splash the surface on two of my data collection visits. Still marking zeros on the actual observation data collection form from the two areas I generally walk so far but I expect to sight herring at some point. I was able to take a picture of one from the shore last season. I have my camera ready.” Bill K. Wethersfield Cove, CT